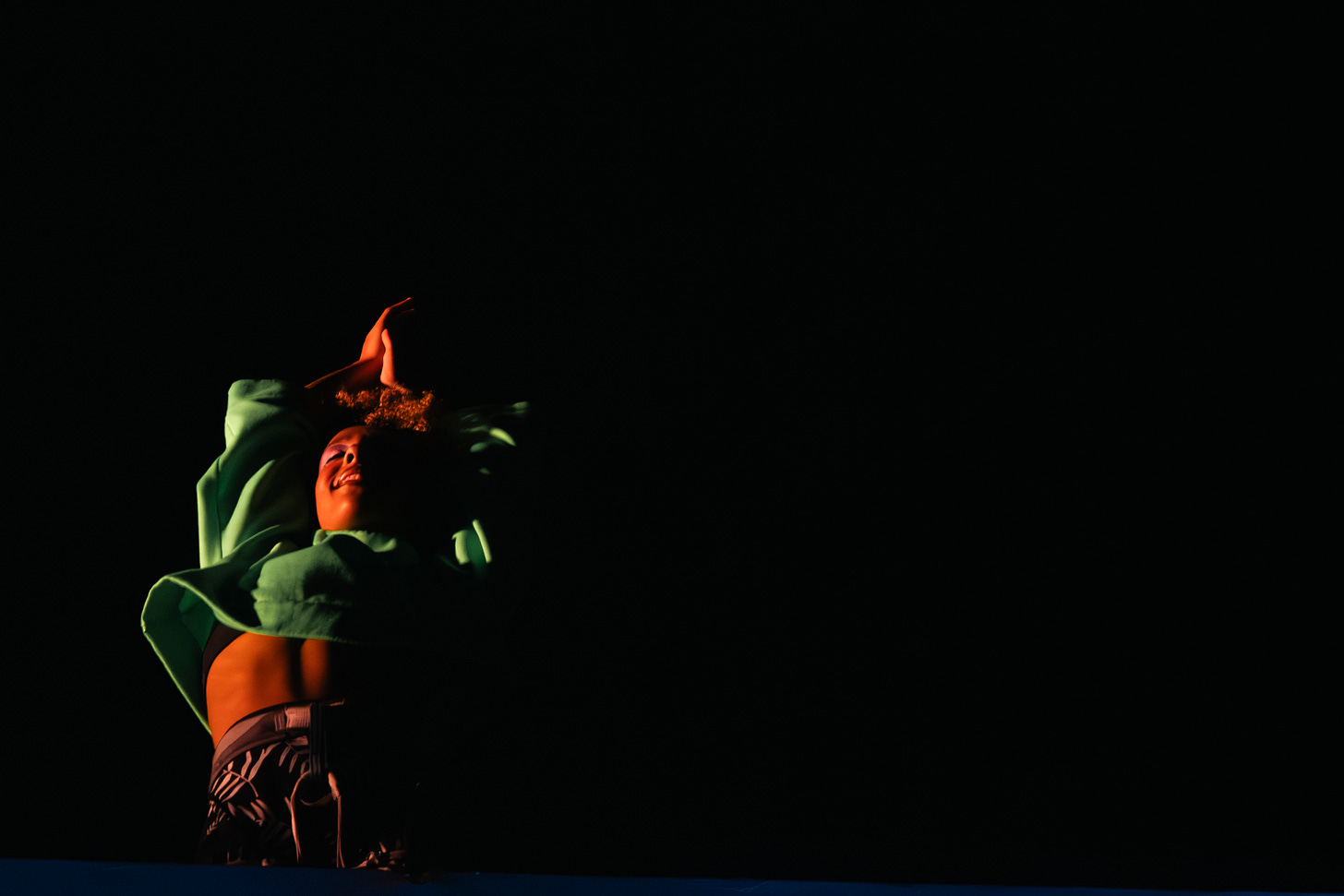

Jhia Jackson in Down on the Corner. Photo credit: Brooke Anderson.

This morning I listened to a Facebook Live Chat between historian Heather Cox Richardson and New York City Mayor Zorhan Mamdani. They talked about expanding the definition of democracy. That it’s not just at the ballot box. It’s on the street; it’s with childcare; it’s the rent and it’s what’s on the shelves at the grocery store. For 30 years I have described my work as the democratization of public space. In 2025, my artistic team and I created Down on the Corner, to honor the site of the 1966 Compton’s Cafeteria Riot and conjure its liberation and a just transition for the future.

Two years ago, the Artistic Director at CounterPulse shared a letter with me that was put out by the TurkxTaylor Initiative (TxT). The letter asked for community support to help liberate the building at 111 Taylor Street by organizing a grassroots social justice campaign. TxT stewards the Compton’s x Coalition, the coalition working to protect and liberate the building. 111 Taylor Street is the original site of the 1966 Compton’s Cafeteria Riot, a response to the violent and constant police harassment of trans and gender variant people. The cafeteria itself was a “thriving after-hours ecosystem of the down-and-out.” The campaign’s goal is to unsettle the structure. In less poetic language, the goal is to remove GEO Group from ownership, acquire the building via community land trust, and “transform it into a forever home for trans, immigrant, and justice-impacted communities.”

GEO Group is one of the largest private prison companies in the United States. Through one of their subsidiaries, they own and operate the building at 111 Taylor which they call Taylor Street Center and claim is a reentry center for incarcerated people, but run like a de facto private prison. They own detention centers across the country. As I.C.E. advances its caging here in the US, GEO Group is growing. They own 97 prisons, detention centers, and reentry centers encompassing 74,000 beds including the facility in Louisiana that was holding, illegally, Mahmoud Khalil—a Palestinian Green Card holder and graduate student from Columbia University. For the third quarter of 2025, GEO Group reported its total revenues of $682.3 million, an increase of approximately 13% from the third quarter of 2024 .

TxT’s community letter moved me. It offered me a chance to be a part of something, and to use my artistic skills to cultivate justice on a street corner. I’ve brought together over a dozen artists—trans, queer, female, systems impacted and survivors of violence. Together we worked with film, projection mapping, original music, and new choreographies to howl, shriek and demand change.

“It’s beauty and fantasy, but it’s not digital. It’s real!”

–Witness on Taylor Street

I am prison systems impacted. This has meant raising my son alone; paying long-term fines and fees necessitated by pretrial, prison, and probation; being judged and rejected by communities for choosing to believe that those who cause harm can heal; and enduring the prison industrial complex in my living room every month during five years of my partner’s probation. I’m also a cisgender woman working inside an intersectional coalition blessed with significant trans leadership.

To the coalition I’ve promised a piece of public art that speaks to the “mythopoetic crossroads” inherent at the corners of Turk and Taylor Street. I’ve called this project Down on the Corner. Because so much living takes place on street corners in the Tenderloin. Because I want the building to come down and go up again as a living space that actually cares for people. Because divesting from a prison economy and investing in community well-being is ripe for this corner. Because years ago trans historian Susan Stryker dug up the unknown fact that in August of 1966, late at night at Compton’s Cafeteria, someone had had enough of police violence and threw the coffee in her cup at a cop who was treating her badly. Because GEO Group needs to go down and this history of resistance needs uplift.

“Throw a cuppa at a coppa…”

–Song lyric by Melanie DeMore for Down on the Corner

What’s deep for me is the timing. I’ve never before created public art about a political struggle while that struggle was being activated in real time, side by side with my creative process. Or no. I have that backwards. The transgender community is in the lead, within a collective framework via the Compton’s x Coalition. I have created the work in real time alongside the transformation of 111 Taylor Street, as justice is being conjured there right now.

The totality of Down on the Corner is born from coalition building. It’s been an honor to be a part of the coalition. The Jurisdiction Hearing I attended and spoke at on May 7th, 2025, in front of the SF Board of Appeals was one of the most inspiring moments of participatory democracy I’ve ever experienced. We packed the hearing. We cut through the belittling that GEO Group’s attorney served up to the appeals board. In small public poems—as we were each only allotted one minute each to speak—the community named some harsh and beautiful truths. That GEO Group treats people with punitive and dehumanizing methods that do not add up to real reentry. That what GEO Group offers is worse than prison. That the legacy of trans resistance on the corner deserves more than erasure. That the Trans Cultural District in the Tenderloin is the only one in the world and what glory it will be when GEO Group is gone. When GEO Group is replaced, via a just transition, to something the city can actually be proud of.

To compound the trauma at 111 Taylor and in the surrounding community, Melvin Bulauan a 44-year-old man, died in July 2025 after being placed at GEO Group. “Less than a week after his arrival at the Taylor Street Center, Bulauan was dead. His body was found on July 14, just a block away,” Eleni Balakrishnan reported in Mission Local. Bulauan’s death has sparked an ongoing investigation by the SF Board of Supervisors into the neglect, abuse and civil rights violations at 111 Taylor Street.

There is controversy about how GEO Group defines its facility at 111 Taylor. Are the people there inmates or residents? Are they there voluntarily? How did Melvin Bulauan die in their care? Halfway out and half way in. I know a lot about halfway houses. My partner lived in one for 6 months, even though he had a welcoming home to come to. They get you that way. They make money off your body. Your bed. For a long time, GEO Group took a percentage of residents’ wages while they lived in a halfway house. GEO has apparently stopped that practice.

There has been a lot of consideration toward inclusion in the coalition. There has been meticulous listening to people who lived in 111 Taylor who are both transgender and cisgender. For me, this is crucial listening. I‘m curious how this effort will seed itself long term, when the task of buying a building, and blending care for trans, prison impacted and Tenderloin folks is daunting. I’m moved by TxT’s robust beginnings.

“What you are doing out here is beautiful. Because of all the chaos, all the abuse here. Watching you all is so soothing. Makes you feel like it’s all going to be OK.”

–Witness on Taylor Street

I directed the process from the street. I used a walkie talkie to stay connected to both the dancers and the rigging crew on the roof. All in, over 6000 people witnessed the process and the shows. A few people ignored us. Some have seen us working in the neighborhood for years. Most people were excited that something cool was happening on the corner. Lenny was one of them.

Lenny arrived here five months ago from Kansas City. He’s been a welder all his life. But his hands cannot do manual labor anymore. He is taking some computer classes at the main library, to shift his work options. He recently moved to SF to be near his sister. He didn’t know anything about the history of the corner. I had a long chat with him at one of our evening technical rehearsals. It was a difficult night. There had been a shooting up the block on Taylor and Eddy. Our street was closed off. Police threw pepper balls to discourage more shooting. There were SWAT teams on the fire escapes at the other end of the street. There was a stink in the air. A sting in the air. No one cares much about violence in the Tenderloin because the people are brown, poor, already discarded. Our current mayor’s strategies for change are carceral and reinforce the Tenderloin as a containment zone. The hostage situation and police action went on until 6:30 AM the next morning. The crew, Lenny and I got stuck behind a barricade, so we had a long night to talk. He is thinking now he may do his final computer project exploring Black history, maybe the corner’s history. It was odd to have such a sweet connection with a stranger amidst gun violence pouring out of an SRO Hotel.

My role with the coalition has been as a cultural worker. I brought together a team of dancers, riggers, designers, as well as composer Melanie DeMore and film maker Leila Weefur. In a month-long residency on the street and via two weeks of live performances, we danced on two sides of the Warfield Hotel, right across the street from 111 Taylor. Using projection mapping technology, we projected Leila’s film onto the Turk Street side of the building and projected onto 111 Taylor as well.

We opened the piece with Nat King Cole’s ‘Nature Boy’ reinterpreted by Melanie DeMore. I chose that song to honor B Dean’s experience as a transmasculine dancer. I asked Sonsherée Giles to listen to what the building saw over the last 60 years, and bring those ghosted stories to us via the sinewy powers of her body.

While researching for the project, I attended a protest at Turk and Taylor Street, as Trump was just taking office and the trans community was standing up for itself. A Two Spirit, transmasculine elder named Holy Old Man Bull opened the event, grounding the participants onto the land. “I don’t want my story to be a sad story,” he said. I took this to heart as I conceived Down On the Corner. We didn’t dwell in sorrow. Instead, I invited the ghosts from Compton’s to speak to us from the strength of their resistance to police brutality. Still, on opening night, as we gathered back in the green room after the first show, dancer Gabriele Christian let me know that tonight they felt the sadness of the story we are telling. In the act of dancing, they felt echoes of brutality and condemnation for not fitting a gender norm.

We hung coffee cups from the fire escape just across from the original entrance to Compton’s. Dancers Jhia Jackson and Gabriele Christian shone like royalty as they tossed those cups around, as if getting ready for the rebellion. We evoked the rebellion of hair fairies who walked the streets in the 60’s. Until 1974, it was illegal for those assigned male at birth to wear women’s clothing. So they decked out as women from the waist up and then wore pants, in order to comply with the law. They were called hair fairies. We evoked smoke and fire, to metaphorically burn down GEO Group and seed in its place a building laced with care. Members of TxT and I interviewed people who had been incarcerated in 111 Taylor. From their stories we culled together a kinetic call for “good food, good music and good company,” which is a far cry from what GEO Group offers people just out of prison.

We met at the crossroads. Melanie offered us an anthem for connection. B, a transmasculine dancer, and Megan, a systems impacted dancer, met in the airspace in front of the building’s center fire escape. Via ropes, harnesses and years of skill building, they dodged railings, window panes and crumbling cement. They spiraled with split second timing. They embodied a connection that was contagious to the audience. They fell in love with each other and audiences fell in love with them. They crossed their own histories with the ghosts of Compton’s, and modeled fearless conviction to the activists now working to transform 111 Taylor.

“They are filling those cups up with the world and pouring it out to us. They are giving it back to us.”

–Witness on Taylor Street

For our finale we borrowed from the Gullah tradition of stick pounding. Melanie has a deep practice of stick pounding and she gifted us with its power: the faster you go, the more you are in your truth. Nine dancers pounded fast on 3 stories of the fire escape right across from 111 Taylor. They thumped. They stomped. They called self-determination in. They sweat. They invoked communion. They broke free and came back to the rhythm as it got faster and faster. TxT organizer Chandra LaBorde had introduced me to the phrase “Liberate Compton’s.” With our bodies, speed, height, suspended coffee cups and a defiance of gravity, we sought liberation. For the neighborhood. For the building. And for the pulsing of democracy itself on the corner of Turk and Taylor.